Remember making popsicle stick towers as a kid? We’ve turned that concept up to 11 with our 17.5-foot PVC impact drop testing tower.

Our research and development of a metamaterial impact absorber for NASA requires testing with realistic conditions to better understand performance at elevated strain rates – like those in crash scenarios.

This requirement demonstrated a need for an impact testing device that would a) replicate the sort of impacts we needed to test, b) give reliable results , and c) not break the bank.

With virtually no commercially available devices that would suit our needs, we decided to do what any good engineer would do – roll up our sleeves and build it ourselves.

Quantifying properties

Typically, materials used to mitigate collision forces have their properties quantified in a lab setting at low quasi-static loading rates. However, real-world impact conditions happen at much faster speeds. We needed a reliable and affordable mechanism to confirm our lab results would translate to real performance.

NASA’s Langley Research Center has determined that an impact velocity of 8.8 m/s is relevant for rotorcraft collisions – so we just needed to reliably replicate this impact speed during our in-house testing.

We decided that since gravity is free, we’d build an impact drop test tower.

Strain rate dependencies for impact absorbing materials

Before we get into building the tower, it’s important to understand the strain rate dependencies for impact absorbing materials. When translating a material’s mechanical properties from measured values to an intended response, we must consider how the measured values might deviate in different loading conditions.

For example, foam – a well-known impact absorbing material – is generally understood to be highly strain rate dependent – meaning its stress response is lowered at higher strain rates.

On the other hand, honeycomb is understood to be more resistant to performance degradation at increasing strain rates.

The differences in strain rate dependencies for these commonly used energy absorbing materials confirms a need to understand how our metamaterials perform at elevated strain rates.

Putting the DIY drop tower together

Now that we understand the requirements and need for an impact testing tower, the next step was design and construction. We took a fairly simple route, creating the drop tower – section by section – out of PVC piping and connectors that we purchased from a local home improvement store.

Constructing the structural tower component out of PVC piping and connectors.

The structure was fitted with a custom-built top section for raising and lowering the impact platen along a fixed vertical path with minimal planar movement.

The base was fitted with attachments to maintain platen positions and reduce any noise-causing vibrations during impact testing. We also fitted the bottom of the tower with an acrylic debris shield.

Finally, the measurement device fitted to the impacting platen was a MadgeTech Shock300 accelerometer capable of measurements ± 300 g at a sampling rate of 1 kHz.

The completed drop tower (left). Impacting platen with accelerometer and guide attachments, lower paten secured and rigid (right).

Calibrating the drop tower

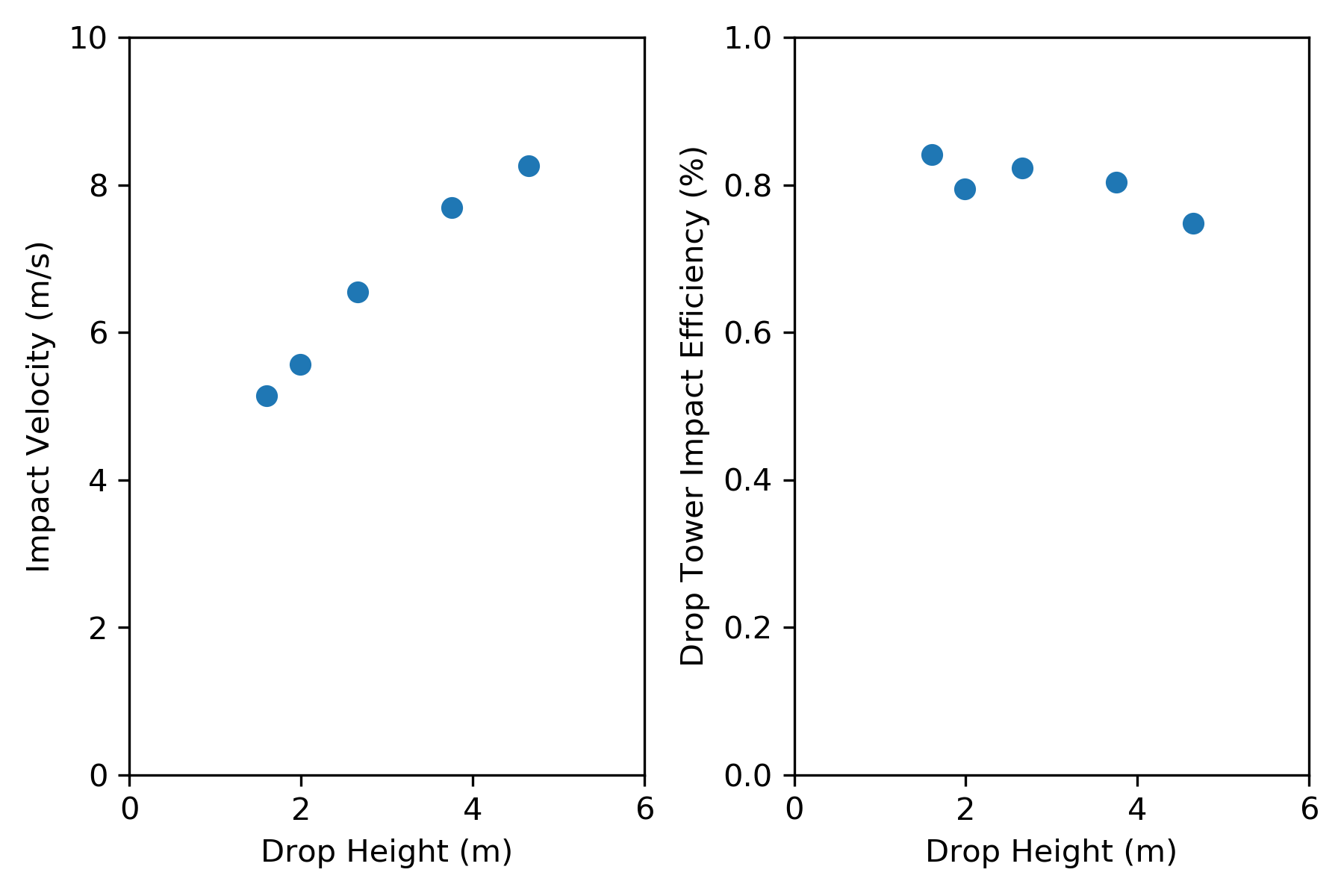

To complete our DIY drop tower, we needed to undertake some calibration tests to determine the expected constants we’d use when taking measurements. By performing a set of calibration tests at varying heights, the system performance can be described in terms of the impact velocity range and the percent of energy converted from potential to kinetic energy.

The impact velocity of the platen as a function of the drop height shows that impact speeds can reach 8.5 m/s (left). The drop tower impact efficiency is described as the percentage of kinetic energy measured at impact over the initial potential energy measure at the drop height.

We determined that velocities could reach 8.5 m/s, which is comparable to the 8.8 m/s determined by NASA Langley’s Research Center. Conveniently, the height for this velocity also keeps us within limits of local fire safety codes.

It’s also pretty satisfying watching the drop tests in slow motion:

Latest Lab Notes

News /

July 18, 2025—Multiscale will engineer functionally-graded alloys tailored for molten salt and liquid metal environments, leveraging its hybrid manufacturing systems to produce nuclear-grade material performance.

News /

March 11, 2025 – Multiscale Systems to showcase cutting-edge industrial innovation during StartUp Week Worcester 2025.

News /

Multiscale Systems receives Massachusetts manufacturing award in recognition of outstanding leadership skills in the manufacturing industry.

Shawn Aalto, R&D Mechanical and Materials Engineer, specializes in material design, simulation, and manufacturing.

Shawn Aalto, R&D Mechanical and Materials Engineer, specializes in material design, simulation, and manufacturing.