At Multiscale Systems we specialize in designing and producing mechanical metamaterial solutions. In this overview, we’ll discuss how mechanical metamaterials – or metamaterial composites as we often call them – differ from conventional materials and what they can be used for, as well as the promise (and occasional pitfalls) associated with mechanical metamaterial engineering.

Editor’s note (August 2023): You may notice in our more recent content that we changed the term mechanical metamaterials to metamaterial composites. They’re still the same thing – we wanted to give them a new name that might be more friendly to those unfamiliar with the concept, since a lot of people will recognize the word composites. We’ve left mechanical metamaterials in some of our older content – like this blog post – so you may come across it on occasion.

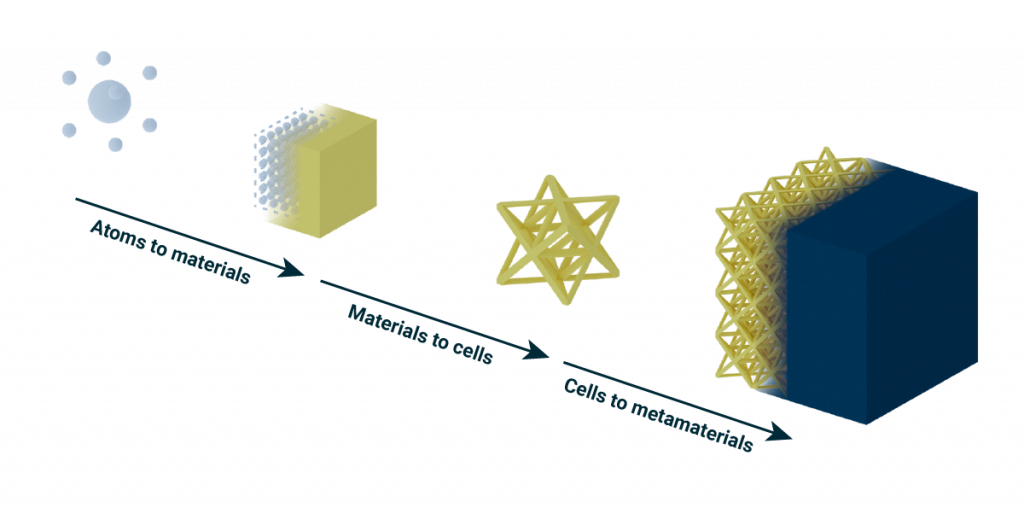

Figure 1: From conventional materials to metamaterials. All conventional materials are composed of constituent atoms. Depending on the type and structure of those atoms, we can get materials as diverse as rubbers, metals, and ceramics – each with distinct properties and characteristics. Taking a conventional material and structuring it on a “meta” scale in the form of a cell allows us to build structured “metamaterials” that are designed to move beyond the restrictions of conventional materials.

What turns a conventional material into a metamaterial?

Conventional materials have mechanical, thermal, and optical properties that are determined by their molecular or atomic composition. Material science usually focuses on how this composition affects overall material properties. Take cast iron, for example. Cast iron is a brittle, hard material that is difficult to work with, but with just a little bit of carbon (and thousands of years of collective metallurgical experience), it can be transformed into steel, which is both strong and malleable.

The building blocks for material science are usually atoms and molecules, with metalworkers and polymer scientists alike combining these fundamental pieces to make an alloy, plastic, or ceramic that is better than those that came before.

Metamaterials takes the idea of building blocks one step further. In fact, the word “meta” comes from the ancient Greek that can mean “further” or “beyond”, and it refers to the fact that metamaterials are carefully structured with building blocks beyond the atomic scale (see Figure 1). Any conventional material can be geometrically architected into a “meta” cell that is then put together in a periodic pattern to make a metamaterial.

The key differentiator between a composite and a metamaterial is that the geometric pattern provided by the “meta” scale is designed for a particular purpose.

Purposefully designed characteristics

Metamaterials are purposely designed to produce characteristics that a conventional material can’t exhibit. Over the past several decades, metamaterials have been created that can manipulate optical, acoustic, thermal, and mechanical properties.

Specific applications include optical materials that act as perfect lenses, perfect acoustic dampeners, negative thermal expansion, and negative stiffness mechanical metamaterials. The field is growing fast as more applications are discovered, and it would be impossible to cover all the innovations in the brief time we have here, but we can dive a little deeper into mechanical metamaterials and explore many of the potential material systems that can be created using geometry instead of chemistry.

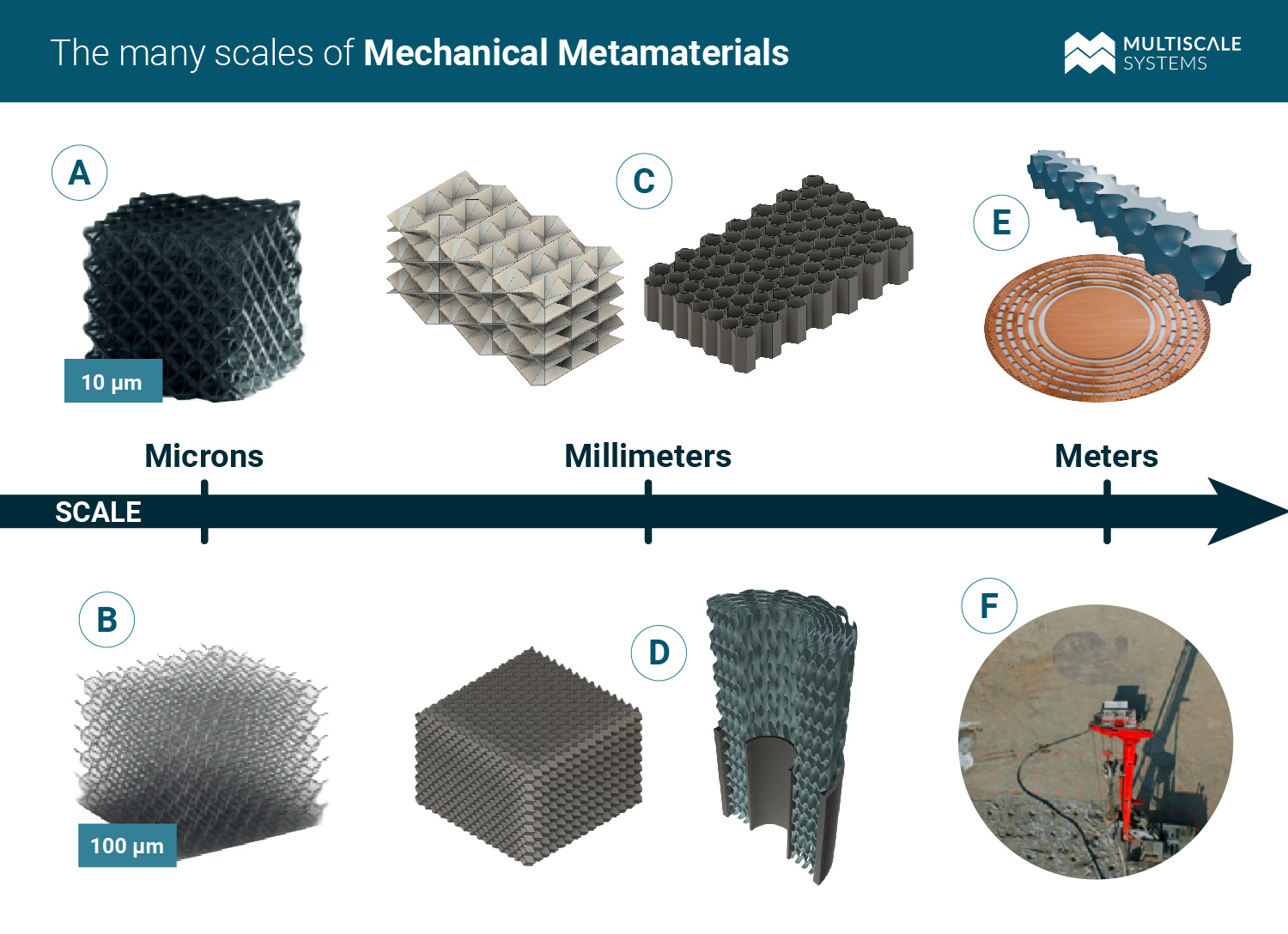

Figure 2: Mechanical metamaterials at many scales. Because they are based on geometry, mechanical metamaterials can be made at any lengths scale. Microscopic lattices can be 3D-printed using a variety of specialty techniques, and can create ultra-light, ultra-stiff lattices1 like that shown in (A), or a material with extreme characteristics1 like that shown in (B). At the millimeter to centimeter scale, the same geometries can be used, or different designs can be implemented for other objectives, like directional stiffness (C) or impact absorption and failure mitigation (D). Dynamic properties can also be manipulated, as evidenced in metamaterials that can act as heat or acoustic shields2 (E) or even larger structures that can cloak buildings from seismic activity3 (F).

What properties can be manipulated by using a mechanical metamaterial?

Mechanical metamaterials can be used as solutions for a variety of problems, since they can be designed for particular applications to replace materials that are commonly used (see Figure 2). The best part of mechanical metamaterial engineering is that you can use both the natural characteristics of the basic material that you are working with in addition to the “meta” geometric design. Here is a list of just some of the advantages of working with mechanical metamaterials:

Extreme properties

One of the hallmarks of a metamaterial is the ability to imbue a conventional substance with properties that can’t be achieved under normal circumstances. Mechanical metamaterials can be structured as a lattice that has isotropic, ultra-light, ultra-stiff behavior (Figure 2A). With a change in the geometry – but without changing the conventional material – the resulting metamaterial could be stiff under pressure, but soft when it is sheared (Figure 2B).

“Negative” properties

Even more shocking than the extreme characteristics mentioned above, metamaterials can be structured to behave to be directionally stiff, or even exhibit negative compressibility (Figure 2C). Alternatively, mechanical metamaterials with negative Poisson’s ratio can be created, no matter the base material. Most materials get thinner when you stretch them, but mechanical metamaterials with a negative Poisson’s ratio (so-called “auxetic” materials) get thicker when they are put under tension (Figure 2D). Auxetic materials can function as energy absorbers and are generally less prone to fatigue than their conventional counterparts.

Multifunctionality

Acoustic, vibrational, and thermal properties can also be affected by judicious application of metamaterial engineering. By carefully structuring the size and shape of the cells, metamaterials can shape the flow of acoustic or thermal energy (Figure 2E), and by joining two or more materials together a metamaterial with negative thermal expansion can be created. With a large enough structure, a mechanical metamaterial can even be created that can protect buildings from earthquakes! (Figure 2F).

We’ve got even more properties that can be customized based on particular needs. Check out our list of characteristics.

What’s the difference between a composite and a mechanical metamaterial?

In many ways the distinction between a composite and a metamaterial is difficult to make. After all, they both involve altering the mechanical properties of a material at some intermediate scale, so what’s the difference?

- Composites mix together strong, lightweight components to achieve a synergistic effect while mechanical metamaterials build their effects directly into each unit cell.

- Mechanical metamaterials are designed in all three dimensions, while composites are generally limited to two dimensional fabrics that are stacked.

The key differentiator between a composite and a metamaterial is that the geometric pattern provided by the “meta” scale is designed for a particular purpose. Foams are lightweight because they are mostly air, and the extremely high tensile strength of a fiber-reinforced composite arises because they are constructed from a strong material, but how do you design a foam or a composite lay-up that has a high stiffness in one direction, but is compliant in another? How would you design a composite to have exact mechanical (and in some cases, thermal) properties? This is where mechanical metamaterial design truly shines.

It is true that many of the objectives of composites technology overlap with the benefits of mechanical metamaterials. After all, the primary advantage of using a composite is that it can provide high strength and stiffness with minimal weight, and this is precisely what some metamaterials are designed to do.

Once a material needs to satisfy several objectives simultaneously, however, mechanical metamaterials can target those objectives specifically, rather than just relying on being lightweight and strong.

This seems too good to be true. What are some of the limitations of mechanical metamaterials?

In principle, since geometry is the key to designing mechanical metamaterials, they could be produced at any scale and still carry the same effects with them. This promises to provide advanced functionality at the micron- and even nano-scale, or up to the size of vehicles and buildings.

However, there are some major obstacles to overcome. The same geometric complexity that allows mechanical metamaterials to transcend the properties of conventional materials also limits their manufacturability. Mechanical metamaterials like those shown in Figure 2A and 2B are both small scale, complex lattice structures, and have to be manufactured using specialized equipment that is expensive, slow, and requires careful calibration to be effective. On the other side of the spectrum, creating building-sized metamaterials involves large capital expenditure and the successful navigation of a wide array of regulatory apparatuses.

The “sweet spot” for producing mechanical metamaterials appears to be in between these two extremes, where conventional materials and manufacturing methods can be leveraged to create mechanical metamaterials at the millimeter to centimeter scale.

How Multiscale Systems makes metamaterials

At Multiscale Systems, we always keep manufacturability in mind when we design our solutions, and this allows for a seamless transition from ideas to fabrication. Our methodology involves designs inspired by origami, the Japanese art of paper-folding; while it may seem counter-intuitive at first, all of our designs start from a thin sheet of conventional material that is then folded and stacked into a multifunctional mechanical metamaterial. This process allows us to take advantage of traditional manufacturing methods, and clear several of the hurdles that usually slow down the efficiency of producing large quantities of metamaterials.

Contact us if you want to know more about how mechanical metamaterials can solve your engineering problems.

References:

- Kadic, Muamer, et al. “3D metamaterials.” Nature Reviews Physics 1.3 (2019): 198-210.

- Kadic, Muamer, et al. “Metamaterials beyond electromagnetism.” Reports on Progress in Physics 76.12 (2013): 126501.

- Aznavourian, Ronald, et al. “Spanning the scales of mechanical metamaterials using time domain simulations in transformed crystals, graphene flakes and structured soils.” Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 29.43 (2017): 433004

Latest Lab Notes

News /

July 18, 2025—Multiscale will engineer functionally-graded alloys tailored for molten salt and liquid metal environments, leveraging its hybrid manufacturing systems to produce nuclear-grade material performance.

News /

March 11, 2025 – Multiscale Systems to showcase cutting-edge industrial innovation during StartUp Week Worcester 2025.

News /

Multiscale Systems receives Massachusetts manufacturing award in recognition of outstanding leadership skills in the manufacturing industry.

Art Evans, Ph.D. is the CTO and Research Director at Multiscale Systems. With a background in physics research, numerical analysis, and computational continuum mechanics, Art leads technology development and research projects.

Art Evans, Ph.D. is the CTO and Research Director at Multiscale Systems. With a background in physics research, numerical analysis, and computational continuum mechanics, Art leads technology development and research projects.